Comparing our QE framework to Lyn Alden's

QE and QT should never be relevant to one's outlook for the real economy.

In this installment of this series, we explore QE in a bit more depth, comparing our approach to Lyn Alden’s view of QE as money printing. As always, the goal of these pieces is to expose our thinking by testing it against those who do a great job clearly outlining their views.

In the first post, we discussed Jeff Snider’s views on the possibility of monetary deflation given the consistently pessimistic outlook priced into asset markets.

In the second post, we discussed Michael Howell’s views on the possibility of excess monetary inflation given central banks’ quick trigger for expanding liquidity.

This will be the last piece available for free - we have a long list of “guests” for this series in the works, so subscribe!

The overarching takeaway from this series is that many of these frequently espoused views actually represent what we consider extreme and highly unlikely outcomes. In response, we are seeking to describe the reality: things are good.

Alden’s characterization of QE (based on this piece from her website) is that when “paired” with fiscal spending, QE funds the federal spending by creating the money to spend. Along these lines, we see the conclusions Alden draws from her perspective on QE as being similarly right-tail, as Howell’s are:

Alden views QE as another meaningful tool in central banks’ toolkits, one that they will not hesitate to use to “finance” ever-increasing public deficits that ultimately produce high inflation, which we must protect ourselves from by buying gold and crypto.

This piece will first outline Alden’s description of the plumbing of QE, especially in the context of post-Covid fiscal expansion, which we think is a good summary of the prevailing narrative of QE’s impact on the economy. We’ll then describe our view of QE as little more than a reserve management tool by central banks that has no effect on the economy.

At a high level, Alden’s QE is true money printing, viewing it as handing the government money that it can spend into the economy. We see those two operations, QE and fiscal spending, as entirely independent and unrelated. Money printing should be instead thought of as “Asset Printing”, and QE does not print assets in the same way that the government does with deficit spending.

Alden’s QE gives the Fed a role in public finance that it does not actually have.

Alden treats QE as one of many ways the government can finance its spending activities. She sees this tool as becoming especially necessary as government debt gets progressively larger.

So what happens when they still want or need to borrow even more, and yet not enough voluntary lenders are available to accumulate Treasuries? When government debt is equal to 100% or even 200% of the country’s entire GDP and still growing, it can be tough to find enough balance sheet space to put all those Treasury securities in exchange for dollars.

In her characterization, QE allows the government to spend new dollars into the economy, whereas every other method of financing government spending involves redistributing existing dollars within the economy.

By creating new dollars to fund the government, QE allows the government to spend money on the domestic economy that they never extracted from the domestic economy or even from international lenders.

If that QE had not been performed, then the same amount of government spending would have extracted dollars from the economy, or else the government spending would have needed to be reduced if they could not extract the dollars due to saturating the lender base. However, because this void of new dollars was created instead, the government spending was able to happen without extracting it from the existing system.

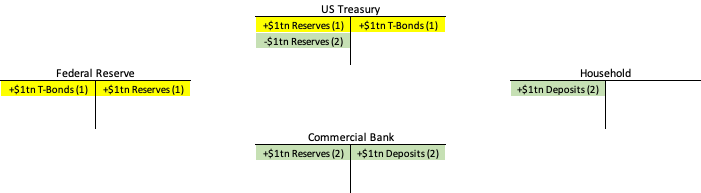

To summarize, Alden’s QE allows the Fed to hand the Treasury money it can use to spend into the economy, making QE a money-printing that can affect the real economy. Below I’ve shown with balance sheets what her view of this operation looks like:

In Step 1, the Treasury issues a bunch of bonds that are purchased by the Fed, which prints reserves and hands them to the Treasury, who plans to spend them.

In Step 2, the Treasury spends these reserves into the economy, sending them to commercial banks and instructing the banks to credit the target recipients’ deposit accounts at those banks.

Combining these steps, we get to Alden’s description of what happened in March 2020: The Fed effectively monetized the post-Covid fiscal stimulus, getting the QE money into the economy and ultimately producing inflation.

We disagree with that assessment. Step 2 (spending) comes before Step 1 (QE), making Step 1 (QE) not necessary for Step 2 (spending).

Our view of QE: Nothing more than a bond-reserve asset swap, disconnected from federal spending.

We like to rephrase QE as QRM, or Quantitative Reserve Management. QE as popularly viewed isn’t an ease. It doesn’t fund the government; it doesn’t print money; it doesn’t affect the real economy. If it did, the QE era wouldn’t have had worse nominal economic outcomes than the pre-QE period, during which the total size of the Fed’s balance sheet never exceeded $1tn.

As an empirical matter, the Fed never monetized the Covid debt, and QE was immaterial to the US Treasury’s ability to fund itself. The CARES Act was funded almost entirely with T-Bills. The Fed did a QE of entirely T-Notes and Bonds without linkage to the CARES Act US Treasury funding.

More importantly, and as the US Treasury’s T-Bill funding vs Fed’s QE purchase of T-Bonds and notes shows, the Fed and Treasury are not coordinated nor collaborating in the funding of fiscal spending.

The creation of the funding for the CARES Act was in the spending of the CARES Act, and then, as a separate question, the Treasury can choose to replace some of that new money with Treasury securities (“borrowing”), or drain some of that spending (taxation). The Fed is prohibited from having any involvement with these processes.

Below is the 3 step process that describes what happened in March 2020:

In Step 1, the government spent new money into the economy. The Treasury asked the Fed to credit household and business bank accounts with additional funds, which the Fed did along with printing reserves to sit on bank balance sheets. When CARES was being discussed and implementing, the “how will we pay for it” question was never on the table. The money was printed, but not through QE, it was just numbers on a balance sheet.

In Step 2, the government then replaced some of this new money with T-Bills. This was again just an inert accounting operation. The government spent $5 trillion in stimulus, PPP, unemployment, etc., into the economy, and then it drained some of that money and replaced it with securities.

This is why whether the government borrows or not is irrelevant to whether or not it prints new money. Money printing occurs when new asset-liability pairs are created on the private sector’s aggregate balance sheet. When the government spends, it adds reserve-equity and/or deposit-equity asset-liability pairs to the private sector’s balance sheet. When the government “borrows” to fund its spending, it still adds new asset-liability pairs; this time it’s just Treasury-equity pairs.

Finally, in Step 3, the Fed, independently and unrelatedly, conducts QE. The Fed replaces some of those Treasury securities with a different kind of security, reserves. Changing the composition of an asset-liability pair isn’t money printing, which is why we don’t consider QE money printing. We see QE as akin to money transforming.

QE only increases money supply measures like M2 because M2 now is defined to include certain kinds of money, i.e. reserves, while excluding other kinds of money, i.e. Treasury securities. So if you replace an inapplicable money form with an applicable money form, then obviously that money supply measure will increase.

If we were to define an “M-TMF” money supply measure as exclusively the amount of Treasury security money held by the private sector, then QE would be money-destroying according to that measure, because it would reduce the supply of Treasuries in private hands.

It’s not any measure of money supply that matters, it’s the supply of total assets that matters. QE doesn’t expand assets because it always removes an asset in the process. Hence, it’s not money printing.

In the QE era, M2 “money supply” diverged from the supply of bank loan-deposit asset-liability pairs, because it was effectively distorted by this form of money transformation.

As always, this QE discussion recenters us on the only two flows we see as important for the economy: fiscal expansion and bank lending. Those are the only two flows that can create new assets for the private sector, so they are the only two flows that are relevant for economic activity. Whether the Fed does QE or QT has no bearing on those flows.

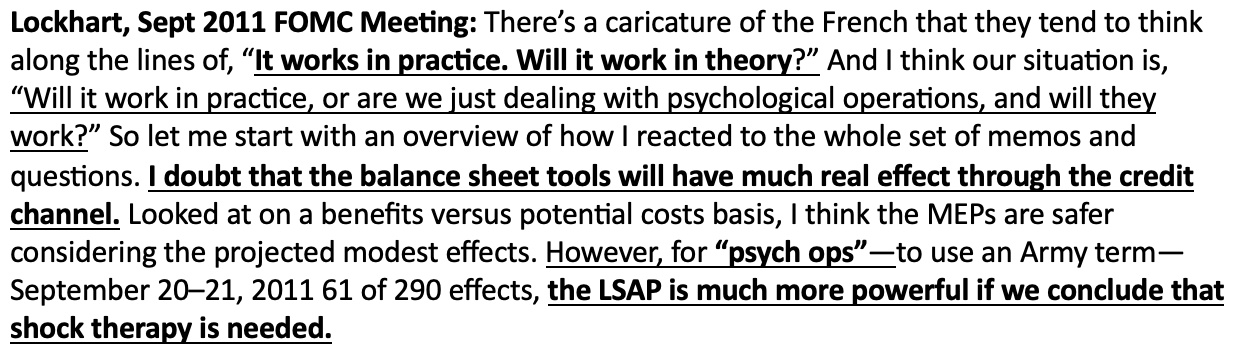

Those flows wouldn’t have been much different had the Fed stood pat. Of course, there is a psychological component to all of this, which is that if the Fed can credibly demonstrate it’s working hard to support the economy and will do whatever it takes, hopefully the economy can respond in kind. But underneath all of that myth-making is the reality that QE has little to no “real effect”. It’s little more than a psych-op, and the sooner we shed the Fed, the faster we can return to macro.

As always, reach out if you have an idea or person in mind you’d like us to add to the queue. Until next time.

Continuing to work my way through the back catalog. Do you have articles discussing the decline in bank loans in 2020-2021? Would you attribute this purely to COVID?

Thank you Ritik and George.

I have just posted to your earlier post comparing to Jeff Snider.

As I said, have some questions, nagging questions if you will after reading this white paper comparing Lyn Alden and TMF :)

So, I was wondering if you can please help with the following:

1. QE. I agree with this "In Step 1, the government spent new money into the economy. The Treasury asked the Fed to credit household and business bank accounts with additional funds, which the Fed did along with printing reserves to sit on bank balance sheets. When CARES was being discussed and implementing, the “how will we pay for it” question was never on the table. The money was printed, but not through QE, it was just numbers on a balance sheet"

a. Question: Why is the FED doing QE (asset swap)? What is their incentive according to you as opposed to doing something else or nothing? Psych-ops?

b. I quote you "QE does not print assets in the same way that the government does with deficit spending."

and

"Finally, in Step 3, the Fed, independently and unrelatedly, conducts QE. The Fed replaces some of those Treasury securities with a different kind of security, reserves. Changing the composition of an asset-liability pair isn’t money printing, which is why we don’t consider QE money printing. We see QE as akin to money transforming."

Question: So, if the FED does QE, it buys bonds from banks (crediting them with inert reserves; banks lose the bonds and the associated income).

I've yet to see someone explain what happens when FED does QE and buys bonds FROM SOMEONE ELSE (Pension Fund, Corporate entity (Apple as example) MMF, Foreign institutions, etc) ? Are they buying from Banks only If FED buys from someone else, other than a Bank, is then the FED printing assets because they are crediting the seller with USD that is SPENDABLE and not a reserve? These entities would not sell treasuries to FED if they can't use the proceeds (if they are inert bank reserves used for settlement).

c. "Combining these steps, we get to Alden’s description of what happened in March 2020: The Fed effectively monetized the post-Covid fiscal stimulus, getting the QE money into the economy and ultimately producing inflation.

We disagree with that assessment. Step 2 (spending) comes before Step 1 (QE), making Step 1 (QE) not necessary for Step 2 (spending).

Our view of QE: Nothing more than a bond-reserve asset swap, disconnected from federal spending."

Question: Hmmmm, I've read the deficit myth and read some other MMT articles. So let's dig in. How would the Treasury spend if their FED bank account is empty? They need the dollars. Is Step 1 the only option according to you for the Treasury to get the FED to credit their account? If that is the only option, then the QE is unavailable for the Gov & the Treasury (to issue new bonds and get reserves).

d. "We like to rephrase QE as QRM, or Quantitative Reserve Management. QE as popularly viewed isn’t an ease. It doesn’t fund the government; it doesn’t print money; it doesn’t affect the real economy. If it did, the QE era wouldn’t have had worse nominal economic outcomes than the pre-QE period, during which the total size of the Fed’s balance sheet never exceeded $1tn.

As an empirical matter, the Fed never monetized the Covid debt, and QE was immaterial to the US Treasury’s ability to fund itself. The CARES Act was funded almost entirely with T-Bills. The Fed did a QE of entirely T-Notes and Bonds without linkage to the CARES Act US Treasury funding.."

Question: Are you saying it is this black and white? "If it did, the QE era wouldn’t have had worse nominal economic outcomes than the pre-QE period" - is it maybe because many beneficiaries of the QE were buying S&P and Nasdaq (index funds, etc) ?

You are saying two different things: "immaterial to the US Treasury's ability to fund itselve" and "doesn't fund the government". Well, even if it is immaterial, let's see how immaterial it is, psych-ops or not. They said they are ready to buy corp bonds in March/April 2020 and they did! They did little buying because of psych-ops I guess and low demand, but still...immaterial or not.

Much appreciated.

Thank you.