Comparing our framework to Jeff Snider's

Jeff thinks markets don’t believe in the Fed’s ability to avoid a recession. We think markets believe way too much in the Fed’s ability to produce a recession.

I thought it would be an interesting exercise to compare our macro framework to Jeff Snider’s, of Eurodollar University. His and our outlook on the US economy sit on opposite ends of the spectrum, and have been since 2022.

In a sentence, our overarching macro view is: “Markets are still, only, just, waking up to the reality of fiscal dominance and its implications for nominal growth, and markets continue to overestimate the Fed’s ability to slow that nominal growth.”

Jeff’s response would be: “Markets refuse to wake up to this reality of fiscal dominance, so it must not be the reality.”

I think spelling out our differences is useful because despite the opposing views, there’s actually some agreement between Jeff and us in terms of how to interpret market price signals, and in what the Fed’s role in the economy is. And interestingly, those agreements often are on points that many others would disagree with.

The big picture is: We generally agree on how market prices should be interpreted and what they are currently discounting. But we disagree on the application of that interpretation, and on how much credit to give those market prices.

How we read what’s priced in

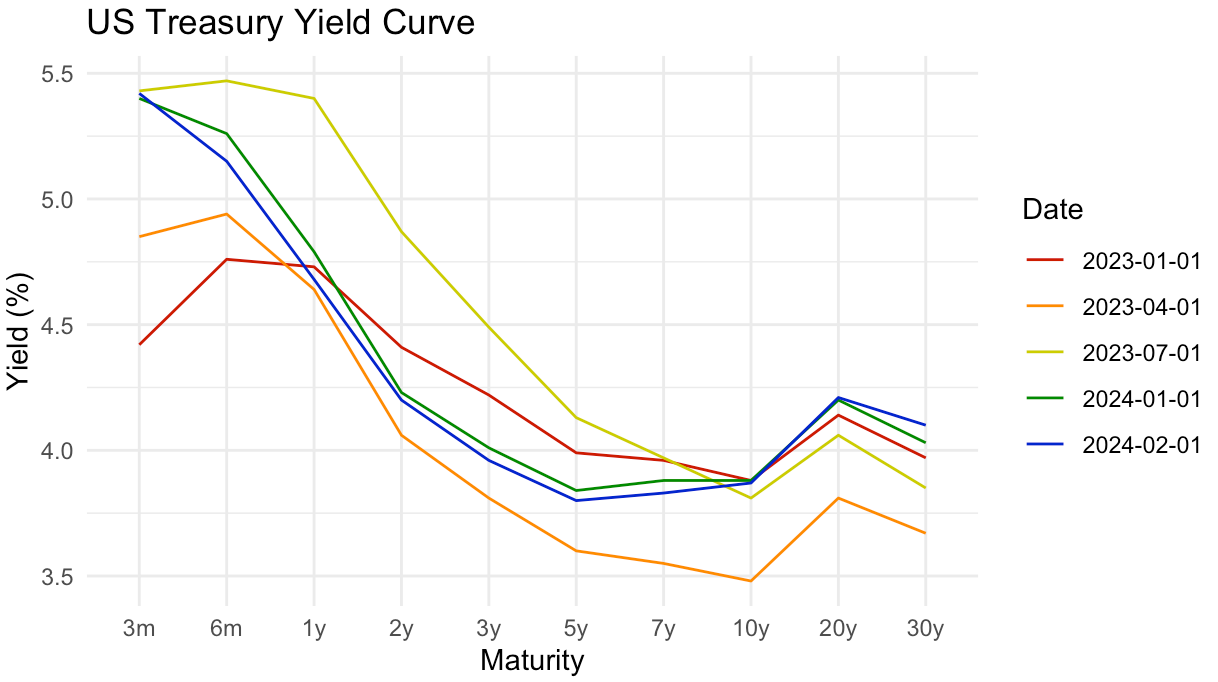

Jeff typically emphasizes the information value of curves like the Treasury yield curve as a signal of real economic conditions. For example, he would ask the below question to frame his analysis:

“Why, since 2022, has the yield curve consistently priced in rate cuts soon after the ongoing rate hikes (via lower 2-year yields than Fed funds rates), as well as structurally lower long-term rates despite the ongoing rate hikes (via lower 10-year yields than 2-year yields)?”

In a sentence, I would best describe Jeff’s answer to that question as: “Markets expect medium and long-term conditions to remain deflationary as they have since the GFC, and markets are rebuking the Fed’s policy of rate hikes as unwarranted and likely to exacerbate those deflationary conditions.”

In other words, Jeff argues that low rates reflect disinflationary monetary conditions, and the inversions of the 3m-2y and 2y-10y yield curves similarly reflect those conditions.

We agree that if you take the Treasury yield curve at face value, it is pricing in deflationary and stagnating economic conditions. We don’t agree, however, on why the yield curve is shaped how it is: we see it as a reflection of the distortive effects of the Fed’s QE, which has dislocated the Treasury yield curve from the true risk-free curve, which is positively sloped and reflects a growing economy.

Not all analysts agree with this interpretation of the pricing. In the below tweet from Jan 2023, Macro Alf lays out the most common alternative view: that markets are pricing goldilocks conditions, not weak conditions:

Our views that stocks will rise more, and that bonds will fall more, arises from our interpretation of current market pricing as reflecting weak conditions, not goldilocks conditions. The difference in interpretation arises from the particular markets we prioritize looking at. More on this shortly.

Jeff and we generally agree that markets are pricing in recessionary conditions. But the below two sentences outline the crucial difference in Jeff versus our application of that answer:

We see markets, especially the US Treasury market rates and resulting curve, as pricing in deflationary conditions, but we think conditions are expansionary.

Jeff also sees markets as pricing in deflationary conditions. But to him, that means conditions are deflationary.

I have 3 reasons in mind for how we end up with that difference:

We favor economic data. Jeff favors market data.

We think the Fed has a credibility glut. Jeff thinks the Fed has a credibility shortage.

We think the rate hikes were an ease. Jeff thinks the rate hikes were not an ease.

Below I discuss each of these:

1. We favor economic data. Jeff favors market data.

All market participants, Jeff and us included, are constantly searching for more and better information about how the economy will be in the future. Jeff prefers to use market prices as his primary piece of information; we prefer to use economic data as our primary piece of information.

That difference in preferences is outlined well in this exchange between Bob Elliott and Hugh Hendry.

Hugh begins the exchange by posing that “a recession is here” on June 25th, 2023:

Bob Elliott disagrees and doesn’t see an imminent recession, pointing to employment and real GDP:

Hugh replies with what doubles as a surprisingly effective outline of his entire macro worldview.

Hugh says he likes what he calls “real variables”. By “real variables”, Hugh means the information provided by market prices, not from statistics like GDP. He goes on, in that same tweet, to give 15 examples of what he means. Below are a sampling of those, verbatim.

Oil curve, people don't want oil for delivery here

Copper, a scarcity that keeps getting cheaper

Industrial metal prices...

Inflation, and yet at the long end, T prices unchanged for last 3 quarters

The yield curve inversion that persists

Risk aversion in stock selection.

The Ponzi scheme embedded in $13 trillion of private equity. New fund launches to buy out expiring funds

Profound risk conservatism at lending institutions

The profound leverage of risk parity that saw intra day "safe" British gilts halve last October

By real variables, Hugh means market prices, and also commercial bank data.

GDP, on the other hand (which Bob points to), is the kind of variable Hugh values less: it’s an “econometric stat”.

Jeff makes a similar point to Hugh: market prices today (in the below case, the yield curve inversion) reflect deflationary conditions, which he sees as evidence that conditions are deflationary.

George sees the inversion not as an indicator of recession, but of the market expecting the Fed to return to the low rate, secular stagnation, low growth world of the 2010s by reducing rates instead of normalizing rates at higher levels.

In our view, market pricing in the present state cannot be trusted for information about the economy, because it now reflects the Fed’s decision to administer rates via QE and forward guidance, which has rendered the information value of the Treasury yield curve almost useless. The “true” curve should reflect forward expectations of NGDP, that is, the economic data should set the market prices, not the reverse.

We see nominal growth and employment data as painting a picture of an economy that is far from recession, and value those indicators more than what the market is saying.

We all agree that the market prices are disagreeing with the economic data. But Jeff and Hugh believe that the economic data is making a mistake, and market prices are calling them out on it. We believe that the market prices are making a mistake.

Why do Jeff and Hugh like “real variables”? Should we favor “real variables” or “econometric stats”?

I think Jeff and Hugh believe that market signals “touch the money” more closely, because real economic players are participating in those markets in real-time, whereas econometric stats get released in a slower fashion and are more susceptible to errors.

But if you’re very confident about the econometric stats you’re seeing, it might be time to disagree with market prices. If you’re confident about the market prices you’re seeing, it might be time to discount the econometric stats you’re seeing.

We at TMF have confidence in the econometric stats like GDP and employment data, but have much less confidence in the validity of the information the market is sending.

Because we think the information the market is providing is invalid, we are betting against the market.

2. We think the Fed has a credibility glut. Jeff thinks the Fed has a credibility shortage.

We agree with Jeff that markets are pricing in broadly deflationary conditions in the medium to long term, i.e. conditions that would by met with rate cuts in the near future. The inverted yield curve is Exhibit A that Jeff (and anyone) would point to.

We disagree, however, on whether the Fed can, or will, actually achieve the conditions that the Fed would respond to by cutting rates, i.e. a nominal slowdown.

Jeff thinks the Fed will induce a recession. We think the Fed cannot induce a recession, i.e. the Fed is dead.

In turn, Jeff thinks the Fed is making a mistake by inducing a recession. We think the market is making a mistake by thinking the Fed will induce a recession.

Where does that disagreement come from? I think it comes from the issue of Fed credibility.

We see the Fed has having too much credibility. Jeff sees the Fed as having no credibility.

“Fed credibility” is an often-discussed idea without a very clear definition. I think of it as: The Fed has credibility if economic participants believe the Fed can get what it wants.

Others often think of credibility as “whether the Fed can achieve a specific XYZ outcome.” I think of credibility simply as how much “Don’t Fight the Fed” ammo the Fed has stored up, regardless of what the particular fight is over.

In this linked piece, Claudia Sahm’s use of “credibility” highlights that difference:

“No one wants to be Arthur Burns, and no one should want to be the upside-down Arthur Burns. Cutting too late, too little, and causing an unnecessary recession would also be a hit to the Fed’s credibility.”

To the contrary, a recession would be great for the Fed’s credibility, because it would remind the system that the Fed can actually get a recession. That is, “Don’t Fight the Fed. Don’t speed up when the Fed is telling you to slow down.”

Instead, it’s only if the Fed doesn’t achieve a recession despite (implicitly) indicating it desires to do so, that would harm the Fed’s credibility.

This is the point George makes in the below tweet, that the Fed has “perjured” itself by failing to achieve its goal, and, unable to achieve its stated goals, there is now no monetary policy.

Monetary policy in the current paradigm is all about credibility. Without it, the Fed’s working model for stimulating or cooling the economy (interest rates, QE, etc.) has been repeatedly shown, since around 2012, the be almost entirely ineffective.

In the face of that impotence, the Fed needs credibility in order to convince the economy to carry out the Fed’s vision for them, because the mechanical policy channels themselves are unable to carry out that vision.

There is no such thing as an “unnecessary recession” as Sahm points to. The ultimate bow in the Fed’s quiver is the cloak of unfalsifiability: we can’t re-run the experiment, so we can’t know for sure if a recession was or wasn’t necessary. And because we can’t know that, the Fed can always safely claim the recession was necessary, and rebuild its credibility using the recession.

The art of central banking is just one skill: maintaining the cloak of unfalsifiability.

Jay Powell masterfully executes the art of central banking in the below quote, from December 13th, 2023:

He says the economy isn’t in recession right now, but it could be in the future, and also, it could be in the future regardless of what is happening right now.

The reason the Fed needs credibility is because credibility helps the Fed get the outcome it wants without the mechanics having to actually produce that outcome. In other words, the larger the “credibility channel”, the less important the actual mechanical effects of rate hikes are in achieving a recession.

We see markets as giving the Fed way too much credibility in its ability to produce are recession. Jeff sees markets as giving the Fed no credibility that it won’t produce a recession.

The dollar strength, weak non-energy commodities, low yields, etc. that Jeff points to are all indeed tearing the inflation narrative to shreds, as Jeff says in the above tweet. But we think they are incorrect to do so.

Jeff thinks markets don’t believe in the Fed’s ability to avoid a recession, we think markets believe way too much in the Fed’s ability to produce a recession.

Because we think the market is making a mistake, we bet against the market.

3. We think the rate hikes were an ease. Jeff thinks the rate hikes were not an ease.

Jeff and we agree on one key interpretation of market prices that many others would disagree with: Low interest rates aren’t an ease, they’re just reflective of weak conditions.

In the below tweets, George and Jeff make that exact point in slightly different words.

Obviously, the idea that low rates aren’t an ease is one that many would disagree with. But that’s why I think there is value to Jeff’s approach, because he gets a few very important and underappreciated pieces of the puzzle right.

Now here is where the disagreement enters:

Jeff is correct that low rates are not stimulus, and that high rates are reflective of strong nominal growth.

But we take those ideas to their conclusion, which is that if low rates aren’t stimulus, and high rates reflect strength, then the Fed should be raising rates, and it’s stimulative for the Fed to do so.

Jeff doesn’t think rate hikes can be expansionary despite agreeing with us that low rates aren’t stimulus and high rates reflect high nominal growth.

Here is how I like to think of the interplay between rates and nominal activity: The Rates-NGDP Binary Black Hole.

The idea is that nominal activity and rates are constantly attracting each other towards each other; and whichever has the stronger pull on the other which ultimately drag the other to it.

So if NGDP growth rises in a robust and reinforcing way, it will overwhelm those who are trying to hold rates low (the Fed, bearish market participants etc.) and eventually pull rates higher.

But there is also the reverse case: If the Fed credibly brings rates higher and refuses to let them fall, it will ultimately have to bring NGDP growth higher with it, to match that higher rate paradigm.

This is the neo-Fisherian idea:

Nominal rates = real rates + inflation. So to raise inflation, one must raise the nominal rate.

We’ve done significant work in the past on the mechanics and empirical evidence behind this.

Jeff thinks the NGDP-Rates Binary Black Hole only works in one direction, that of NGDP to rates, where rates have no gravity themselves. We think the Fed can give rates gravity if it chooses to use them in the correct way. Which is to say, not the way it currently uses rates.

Jeff thinks rates will be lower because rates were made higher. We disagree with the market’s insistence that rates will be lower because the rates moved higher. To express that thesis, we bet against the market.

Final thoughts

The key difference between us is a difference in how much credit we give markets. Jeff thinks markets, while sometimes wrong, are our best shot for understanding what’s going on. We tend to think markets are much more fallible.

Jeff prefers market signals (“real variables”) from markets that are tied in some way to real economic activity: Treasuries, oil, etc. He rarely points to equity markets, as he sees them as providing less useful information about the economy.

This tweet of his from June 2023 illustrates this:

We think all markets are susceptible to making mistakes, and happen to think both stocks and bonds are making a mistake today. To express that thesis, we buy stocks and sell bonds today, expecting stocks to be higher and bonds to be lower tomorrow.

If folks like these deep dive comparisons between our views and others’ views, let us know, and we’ll do more soon.

Suggestion for next comparison: Michael Howell (@crossbordercap)

Beautiful post, keep it up!